Dave Leichtman is the Democratic Strategist for Microsoft’s Campaign Tech Services and the Vice-chair for Tech of the Democratic Party of Virginia. Read Dave’s previous work on Epolitics.com.

As Colin noted last week, much hay has been made over the Democrats’ End-of-the-Quarter “Email Deluge” concluding on September 30th (though I say “conclude” lightly). We saw accusations of maleficence from Trilogy’s Steve Olson and impassioned appeals to our inner organizer from Rising Tide’s Stephanie Grasmick. Whether dissing or defending, it seems everyone has an opinion, but many of them have been light on data and details. And while it’s easy to say “I don’t like all the email,” it’s equally easy to reply with “But it works!”

And does it ever. Organizations like the DCCC, DSCC, and the DNC are setting new fundraising records every quarter. All data points to the fact that more email equals more money and that the tactics they’re employing work quite well. But a closer examination of the details of mass emailing and email deliverability point to two inevitable facts: 1. these “Big Email” programs are potentially damaging the larger Progressive fundraising ecosystem, and 2. the success seen to date can’t possibly last forever.

Network Effects

Taken singly in the context of one campaign or org, it’s easy enough to show that sending more emails raises more money (maybe – more on that later). But that fails to recognize that the big email programs don’t exist within a vacuum. Each of them represents a portion of the total fundraising ecosystem that also includes individual Democratic campaigns and Progressive nonprofits. Their habits have effects across the board – network effects. Let’s examine a few of these effects and how they can negatively impact the fundraising of other orgs.

Brand Erosion

Because these large email programs signify such a huge chunk of the Democrats’ fundraising operation, they also tend to be seen as the outward facing manifestation of the “Democratic Brand.” And while it’s almost certainly true that people who complain about too many emails still donate and still vote, it’s also true that some of them are journalists and some of them write articles that persuadable voters read. Every time we pass an end-of-quarter date, and every time these articles reach fever pitch about the Dems’ massive and over-the-top email fundraising operations, the more it erodes the average voter’s trust in the larger Democratic Brand. And sure, it’s hard to define “over the top.” But when you have your own Tumblr parody blog, you’re probably over the top.

The Wash-out

Imagine you’re interested in a small Congressional race in your hometown, and you’re intrepid enough to sign up for your candidate’s email list. In a potentially misguided attempt to build his own email list, your candidate decides to swap lists with the candidate next door. Only that candidate was actively shopping for lists because that candidate is a DCCC “Red to Blue” candidate with insane fundraising quotas. And she, in turn, then dutifully sacrifices her email list to the larger DCCC list. Now you’re on three lists, and holy crap this is not what you signed up for. Now, on September 30th, instead of getting one or two emails from your candidate who you really care about, you just got 41 – 20 from the DCCC, 20 from the candidate next door, and only 1 you actually care about. But because you’ve been so busy fending off the other 40 emails, you missed the one you actually cared about, or it went into your spam folder. Too bad – your candidate could have really used that $50, but the DCCC wanted $5, and it wanted it more.

Pile-Ups

Take the above situation and add on all of the various orgs who feel the need to push end-of-quarter fundraising, and you’ve got so much email concentrated in so little time that it’s been known to slow down or crash the mail servers of some of the larger Email Service Providers (ESPs). There’s no question that driving fundraising around dates is effective, but when everyone is forced to pile on to the same dates, the dilution is magnified. In fact, the nonprofits have become so swamped by the political end-of-quarter fundraising that they’ve gone and created their own fake holiday date, just to have a date of their own around which to organize fundraising. It’s called Giving Tuesday – the Tuesday after Thanksgiving (Black Friday, Cyber Monday, Giving Tuesday, get it?!), and it’s been growing in popularity over the last 3 years.

Bad Habits Hurt Everyone

And now we get to the ugliness. While I’ll stop short of calling them “spam” (and it’s unfair to lump them all together), many of these large email programs have similarly poor list management practices and display many of the same sorts of bad emailing habits as spammers (don’t shoot the messenger). I’m not here to comment on the value of that statement, only to say that many of the email providers (Microsoft, Google, Yahoo, etc.) don’t much care for those habits. In fact, they often block the receipt of those emails on a massive scale. Around an end-of-quarter deadline, some of these large programs can see their inbox displacement rates (the amount of mail either not delivered or sent to the spam folder) reach double-digits.

Lest you think this affects only the sender’s rates, think again. The big email providers have started dinging the ESPs as a whole for the bad practices of some (and not just limiting the hit to a single server’s IP address). To wit, a spam trap (booby-trapped email address meant to catch spammers) triggered a listing on January 31, 2014 for Blue State Digital on the SpamHaus Block List to which most of the biggest providers subscribe. For several hours in the middle of the day, DNC, DCCC, OfA, and EMILY’s List saw their email inbox placement drop to 50%, not necessarily by any fault of their own.

The big email providers have started implementing their own internal controls, beyond the simple spam folder, on mass email sends that exhibit poor behavior – and remember, they get to define poor behavior, not us. One such practice is grey-listing, where emails are placed in the user’s inbox at the provider’s leisure, sometimes a day later. Ever send a mass email only to have it show up in your Gmail inbox 4 hours later? That’s often why, and it’s usually the result of poor “list hygiene”; that is, sending emails to lots of people who never open them.

Does It Actually Work?

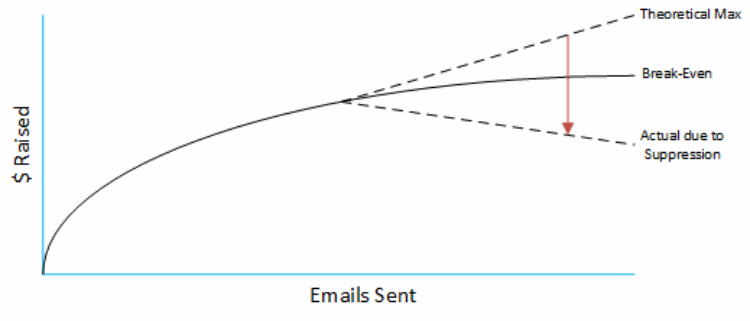

So, knowing that bad email habits can seriously impact inbox placement, one has to ask, does sending more email actually work? In theory, yes. But even the largest email programs often lack insight into inbox placement. They are easily able to access complaint rates (# of people marking spam) and unsubscribe rates, but the inbox placement rate is more subtle. Often, it requires subscribing to an expensive service like ReturnPath which is out of range for any small program. The “real” calculus goes something like this:

The big question for any program then becomes, is the effect due to suppression greater or less than the break-even point? That is, if a program sends enough emails will their lack of inbox placement result in lost money from those donors who never saw their emails? That’s an open question, and one that I submit hasn’t been thoroughly tested at scale and especially across multiple organizations (more on that later).

It Can’t Last

Now for the scary part. None of this is sustainable, and the potential success these large programs enjoy can’t possibly last. Here’s a few reasons why:

Sneaky Devils

You think you’re sneaky, eh? Well, let me tell you, the big email providers will outwit you every time. And in the end, remember that they’re the ones who decide whether or not to deliver your email to the end user. There’s been a recent trend of people putting O’s (oh’s) instead of 0’s (zeros) in fundraising amounts – i.e. the Koch Brothers have given $42,OOO,OOO rather than $42,000,000 – the theory being this evades the spam filters. News alert: it doesn’t. I’m sad to say (and believe me it pains me to do so) that you’re not smarter than Yahoo or Outlook.com. Their filtering will get better and better, and our ability to outwit those filters will diminish more and more. This is a battle you cannot win.

Three People

Deliverability is often a hands-on management task. You don’t see what goes on behind the curtain, and for the most part, you shouldn’t have to. But for the purposes of this discussion, know this. The fact that any political org’s emails actually arrive to their intended target is due in large part to a ton of manual work by three people – the email deliverability specialists at NGP VAN, Salsa Labs, and Blue State Digital (the ESPs that handle a solid majority of all Dem political email). Most of the work of clearing minor blocks that come about due to bad emailing habits is manual and cumbersome (it involves a lot of filling out web forms and begging for forgiveness from the right people). And some of the success is even based on personal relationships. Pray that none of those three ever gets tired of what they’re doing or gets hit by a bus.

The Boogeyman, Part 1 – CASL

Back in July, Canada introduced their own version of the US’s CAN-SPAM law, the Canadian Anti-Spam Law (CASL). But where CAN-SPAM makes exceptions for nonprofits, and hence political campaigns, CASL does not. Now I’m going to tell you something that may surprise you: you have Canadian citizens on your list, and you don’t know it. The problem is that if you can’t prove they got there organically and via confirmed-opt-in (they receive an email and positively identify that they wish to be on your list a second time, and it’s the correct address), then the Canadian Government can levy enormous (read: millions) fines against your org. Granted, they haven’t yet, and they’ve been slow to enforce CASL, but the honeymoon won’t last forever. They’ve sunk a large amount of money into the launch of this law, and they will soon want to make their money back and show it was worth it.

The Boogeyman, Part 2 – SpamHaus

And then there’s SpamHaus – an international anti-spam organization based in Germany to which all of the large email providers give institutional backing. SpamHaus’s block lists are definitive, extreme, and there is no appeal or recourse (officially, anyway) until after the damage has already been done. If they decide your emails are spam, they are, and there’s very little you can do about it. Were the volunteers at SpamHaus to decide to block, say, one of the presidential campaigns, they could see their delivery rates drop by as much as 75-80%. And that’s not alarmist, that’s a fact. They don’t do this on a whim, but rather after gathering a lot of data, such as spam trap hits mentioned above. We’ve had small tastes of their blocking power (and even big ones like with the DGA 4 years ago), but I shudder to think what could happen if several of the large Democratic email programs or one of the large ESPs incurred their wrath.

What Now?

Hopefully I’ve scared you a bit. Are we dangling on the edge of an email precipice? No. But we are walking a fine line, and going too far could have serious and detrimental effects on everyone’s ability to raise money in the Progressive sphere. The good news is that all is not lost, and there are things that we can do, as a team, to walk back from the edge.

Testing

First, let’s do some testing. The network effects I’ve outlined are real, not theoretical. But it will take a coordinated test across many different Dem politicals and Progressive nonprofits in order to gauge the real impact. It would be easier than you might think given the broad client base among the big ESPs. Any one of them would be able to coordinate tests of these effects, it demands only the will and a sufficient case to do so.

Email Smarter

This concept comes in many forms – it’s been referred to recently as optimizing toward other factors like brand loyalty. But in the end it boils down to truly engaging supporters. Bulk analytics within massive email operations has had the effect of causing organizers to lose sight of the end goal – engagement. But why engage the user when torrents of bulk email are cheap and easy?

It’s easier to panhandle than to work a room and shake hands. And in today’s digital world, it’s even easier to panhandle on a giant scale and call it grassroots fundraising. But ask a career fundraiser, and they’ll tell you that working a room and leveraging personal relationships gets bigger checks. Likewise, engaging users might get fewer donations, but it will garner bigger ones as you focus on those who care and want to engage. I’ve seen a well-groomed local email list with 1,000 members raise $1,000 from one email because the people on the list were sufficiently engaged – they wanted to be there, they cared about the candidate, and the candidate made a genuine effort to connect. Seems like small potatoes, but with the current state of data management, it’s now possible on a large scale.

With new technologies being worked on for the 2016 cycle by Microsoft, the political tech firms, and the political analytics and strategy groups, it will be possible to know – in a fully integrated fashion – everything about everyone on your list, all in one place. The only question is, how will you use that data? I suggest that we all start looking at better ways to leverage that data toward micro-targeted engagement. If you know somebody cares foremost about environmental issues, send them an email about that instead of a generic non-donor fundraising segment. You might be surprised at the results.

Email Fundraising Best Practices

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t end with a note about best practices. Whether you took the core message of this article to heart or not, we can all do better when it comes to emailing habits.

Here’s a list of some best practices for emailing from NGP VAN’s email deliverability specialist Brett Schenker:

1. Real-time monitoring – Pay attention to the results of your email. You’d be amazed at the amount of people who have contacted me about delivery issues and questions weeks or months after they occur. If you notice opens or clicks are low, search to see if it’s due to a possible block (you’ll see high amounts of bounces), going to spam, or something else. If you see any of this happening, the answer isn’t to send more email. Try to fix the issue first or you’ll just exacerbate the issue(s).

2. Counterprogram – While I understand that the urgency of end of quarter drives people to give, think about emailing at a different time, or with different asks. There is a deluge of email now, with more being sent and delivered than ever before. You need to stand out from the crowd, and that could mean emailing at a time you never thought of. Many have found success by sending when no else does.

3. Don’t copy others – Email filtering systems are brilliant, and smarter than you think. They make millions of decisions in a fraction of a second. They not only look for key terms, but also context. With so many sending similar messages at the end of quarter, systems are learning what people do and don’t want. Your message might be going to spam because another campaign that was sent before was very similar and folks didn’t like it. We talk about the impact on each other, and this is one of the ways it happens.

4. Micro-target – I can’t stress enough that messages should be tailored as much to the individual as possible. If you want an example look towards Amazon’s email program and what happens after you browse items, you often get a follow up email with those items a few days after. As mentioned earlier, if you know what issues someone is interested in, use that data to decide what to send, or what the message should be. If someone has never donated through email (or ever) consider another ask beyond a fundraising one during your next push. Past behavior is a good indicator of future behavior, and you have data you can leverage to make your asks personal and effective.

5. Cut your inactives – The top issue when it comes to political email is not the text of the email, it’s the lists being sent to. A key metric ESPs use to determine what to do with email is the addresses you’re sending to, and the users’ past behavior. If too many are ignoring the email, don’t log into their accounts, or just delete the message without opening, you’ll see the amount of email being placed into the spam box increase. Working with many orgs, I’ve helped trim lists, sometimes by 50%. The results are often more total opens and clicks and more money raised. Counterintuitive but true. If list size is your key metric, you’re doing it wrong. Engagement – not just clicks but conversions and actions – is key.

Conclusion

No matter what side of the debate you fall on, it’s hard to deny that there are real, practical consequences from the massive level of emailing we’ve witnessed in the 2014 cycle, especially around the September end-of-quarter deadline. There are detrimental network effects and a mountain of evidence suggesting that the current levels of success can’t last forever. My hope in writing this is to call the issue to the attention of those who might be able to affect a change. Let’s do the tests, let’s address the real problems, and let’s move toward better engagement and better emailing practices. The movement as a whole will benefit, and we might actually continue to raise a lot of money while genuinely engaging list members in the process.

[…] practices create brand erosion, wash out of smaller campaigns, and e-mail pile up as noted in the E-mail Gauntlet. Campaigns need to use analytics, as noted in the Tale of Two Analytic Programs, to ensure that […]

[…] office toward harnessing the power of the Senator’s inbox, implementing some vague semblance of Leichman’s best practices. He would receive nearly 1,200 emails a day. We started categorizing them. Before I understood what […]

[…] of the role of data and analytics in contemporary politics. In his article on email fundraising  Leichtman writes, “I can’t stress enough that messages should be tailored as much to the individual […]

[…] also having a hard time finding a real problem with how the Democratic are operating right now.  Dave Leichtman may be correct that the Democratic Party can’t rely on email fundraising for much longer, but he […]

[…] term remains to be seen, but it’s reasonable to propose that campaigns and committees at least consider down-the-road effects of their work to win this year. I suspect that this particular conversation has barely […]

[…] There’s also a free option out there, partnering with other like-minded organizations or campaigns and doing a joint action or swap. But you must be very careful with this technique: once your list is substantially shared with another organization, then there may be all kinds of unforeseen effects. Is the other group or groups going to share it further? Will they treat the list with respect? This is a quick growth source but it can open up your supporters to mistreatment if you are not careful. More about the possible negative network effects. […]

[…] There’s also a free option out there, partnering with other like-minded organizations or campaigns and doing a joint action or swap. But you must be very careful with this technique: once your list is substantially shared with another organization, then there may be all kinds of unforeseen effects. Is the other group or groups going to share it further? Will they treat the list with respect? This is a quick growth source but it can open up your supporters to mistreatment if you are not careful. More about the possible negative network effects. […]