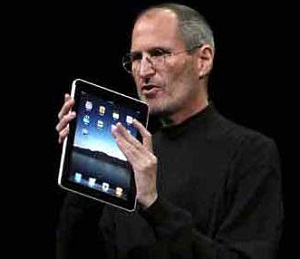

Check out my cool new toy!

The time was early 2010: the iPad had just debuted, Glee was soon to hit TV screens for the first time, and the universe reeled from the knowledge that Michael Jackson was still dead. In the political world, Scott Brown had just joined the Senate, Obamacare would soon be the law of the of the land, and it was beginning to look like the Tea Party might help Republicans in November.

In the digital politics realm, “How Candidates Can Use the Internet to Win in 2010” (the spiritual predecessor of the current Epolitics.com ebook) had just appeared in its second and final edition. Which raises a question: what’s changed in four years? How are online politics and digital advocacy different now, and why? I went through the 2010 book this week to look for some answers, and here’s what I found. To the Wayback Machine!

First, a quick caveat. I did my best to separate the question of “what did I know in 2010” vs. “what did the political world know in 2010,” since the former says more about the ignorance of my youth than it does about the state of internet politics four years ago. And, the new ebook is more than twice as long as its ancestor, because it covers more topics in much more detail. With that in mind, here’s what I found:

What’s Changed:

- In 2010, MySpace still mattered, apparently, because I mentioned it a lot more than I remembered. Obama HAD used it extensively in 2008, so perhaps it still seemed relevant at the time…though it was clearly on a downward slide. In practice, social-network marketing in 2010 turned out to be all about Facebook, despite some hype around FourSquare and other location-based apps. Those were innocent times: the great Facebook content algorithm traffic drought was years away….

- Twitter was still optional, and Twitter advertising was nonexistent. Twitter hype was running full-on, I recall, but at least at the start of the year, diving into that particular social space still wasn’t a must-do for your average campaign for mayor or state legislature. The 2014 book has a long section on Twitter tactics and a sizable one on Twitter advertising, by contrast.

- Online advertising was focused on Google. We’d already seen some use of Facebook ads by campaigns, but it was still a new thing for most. Banner ads had been around for years, but they suffered from the lack of the targeting options that now let campaigns hit individual voters with relevant messages. Back then, display advertising was a more scattershot affair from a political point of view, unless you were advertising on a network like Yahoo or AOL that had demographic data on its members. Many political people saw banner ads’ low response numbers and wrote the channel off entirely.

- Remember the “Google Surge”? In 2010 you could still “take over” Google advertising and dominate a defined geographic region, for a day or so at least. Ever-increasing ad volume has rendered that tactic obsolete, though taking over specific publications in a state or district is still valid and useful (as we’ll discuss in the next “Technology Bytes” column, btw).

- Apps for mobile-enabled field organizing were popping up, having just played a role in the Scott Brown/Martha Coakley race that January. In 2014, they’re everywhere.

- Blogs were higher up the outreach priority list, I suspect in part because of lack of competition. As more and more publishing channels became popular, from Twitter to Instagram and Tumblr, blogs saw a relative decline in popularity and influence, though they’re still a significant factor today.

- The basic principles behind political websites were similar to those today, but integrated political web hosting packages were more rare, particularly for Republicans. DLCCWeb put Democratic candidates on Salsa, but NationBuilder was yet to make a mark, and low-end tools like ElectionMall found a lot of use. Nowadays, integrated CRM/Web hosting packages are robust and solid, and many vendors have their own in-house flavors.

- The book mentions data in passing, in the context of email stats like open rates, but did not address data modeling and data-targeted outreach. The 2014 version has sprinkles mentions of political data throughout, along with an entire chapter on data and analytics. A/B testing email subject lines? Rare for most of us in 2010. Connecting a voter file to Facebook to mine supporters’ social connections? Unheard of.

Still Timeless

Okay, those are the big changes. What’s stayed the same? A lot! Here are some of the biggies:

- Most of the basic principles. Concepts like the power of targeting your online communications at the right people with the right messages, the key role of content in outreach and the need to integrate your communications across channels? These and many more of the fundamental ideas behind the strategies described in the book haven’t changed at all.

- Concepts behind voter mobilization. Most of the changes have been in the tactics and the delivery channels, not the strategies behind their use.

- The basic rules of campaign video were already established, but video advertising wasn’t yet common — it didn’t even get a serious mention.

- Online-enabled peer-to-peer outreach was already seen as a powerful tool — Obama ’08 had demonstrated that, at the very least.

- Online fundraising, interestingly. Email was king then, and it still is. And, the rules of thumb for persuading people to give money via email haven’t changed much since as far back as 2008, even as the number of organizations relying on their email lists for cash has grown dramatically.

Plenty of other details remain the same, too, but here’s a final Big Idea that hasn’t changed one bit since 2010: that the internet is a powerful way to influence politics. The Epolitics.com community has believed it since 2006, when the site launched and readers like you started to come calling. Thanks for being a part of the ride — I suspect it’s a long, long way from over.

– cpd